How does Blue Gum Community School differ from other schools?

(our most frequently-asked question!)

The answer is multi-faceted; different people will highlight different aspects, such as –

- our high expectations and view of each student as competent, capable, creative, responsible, resourceful & resilient…

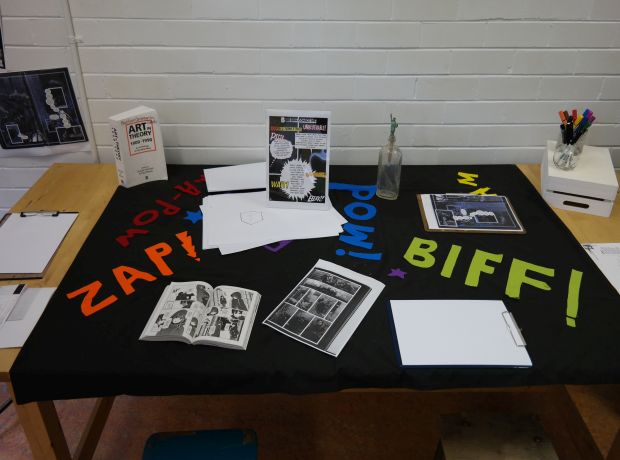

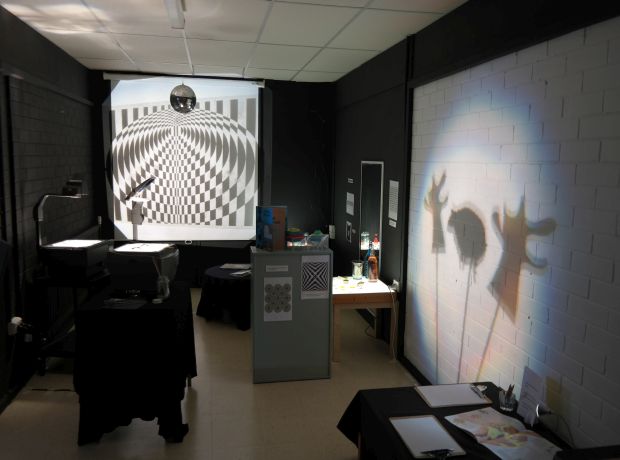

- our tantalizing physical learning environments…

- the extraordinary passion and dedication of our educators…

- our strengths-based research-focused curriculum approach…

- our emphasis on authentic ‘real world’ learning, wherever possible…

- our deliberately-planned multi-age class community structure…

- the time we spend nurturing supportive, respectful relationships…

- our ongoing two-way dialogue with parents/carers…

- our insistence on the Arts, Outdoor Education and Scientific exploration for all students…

- our smallness enabling unlimited customized learning opportunities…

- the value we attach to our Australian inheritance and context…

- our advocacy for children and young people being visible as active citizens in the broader community…

Blue Gum’s educational approach is inspired by and draws on many sources, which are critically evaluated with our students and our community context in mind – a never-ending journey. Influential reference points include:

The Reggio Emilia Experience

The early childhood schools in the city of Reggio Emilia in northern Italy were hailed by Newsweek in 1991 as “the best schools in the world”. Schools worldwide became interested and were inspired by their way of thinking. It was at the end of the Fascist dictatorship in Italy, and after the destruction caused during World War II, that families there decided they wanted to provide a more positive future for their children. In some cases, they converted deserted buildings into preschools; in others, they built new preschools themselves. They were determined to create wondrous learning environments that would restore a sense of hope in the community. Their perseverance in the face of adversity struck a chord when we founded Blue Gum.

The Reggio Emilia experience is NOT a formula or a recipe – there is no instruction book to refer to for the answers. For many educators, the Reggio Emilia experience inspires them where other educational ‘gurus’ have not, because it is a dynamic educational approach. It involves constantly questioning oneself, changing, and inventing new ways of understanding and supporting high-quality students’ learning, educators’ development, and parents’ participation.

So what distinguishes the Reggio Emilia experience?

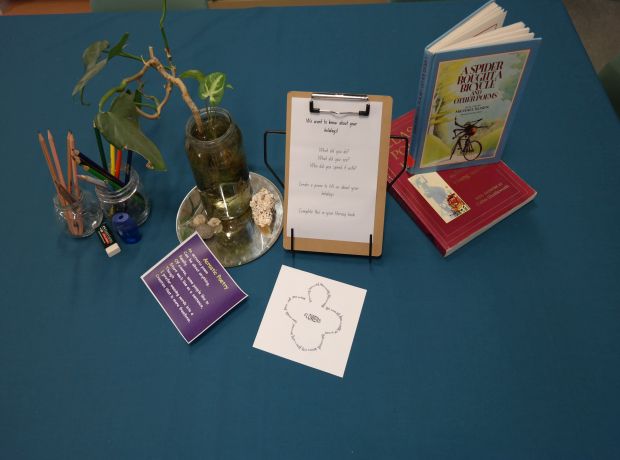

- Negotiated Emergent Curriculum – Educators offer carefully-prepared intent-ful learning ‘provocations’ as starting points to stimulate students’ investigation; then closely observe students’ responses – their dialogue/questions/challenges/discoveries. Often this ever-changing curriculum will emerge from and be informed by contemporary societal events/issues. A pedagogy of listening (rather than instructing) provides informed guidance in identifying powerful entry points for research and further learning. Students’ engagement, discussions and negotiations influence the directions pursued. However, the educators’ role is pivotal in identifying and negotiating deep rich learning opportunities, rather than simply following and indulging the fleeting whims of students. [In the Australian schooling context, learning outcomes will also be linked back to the Australian Curriculum, whether prospectively or retrospectively.]

- Research Project Work/Research Learning Journeys – Here the term ‘project’ refers to in-depth studies and research into concepts, ideas & important questions. Because the outcomes are not pre-determined, but evolve, these Research projects/learning journeys can continue for many months. Getting ‘side-tracked’ along the way, into all sorts of unknown territory which the students encounter and uncover, is seen as a major strength of this approach. Different students will be fascinated by different aspects of the journey and choose different ways to approach it. This flexibility ensures that all students, not just a few, are motivated to learn. Blue Gum educators prefer to use the term ‘Research Learning Journey’, as it aptly describes how we view the process. Unfortunately, the term ‘project’ often elicits memories of superficial cut-and-paste posters undertaken as homework with [by?] parents, thereby giving this term a bad press!

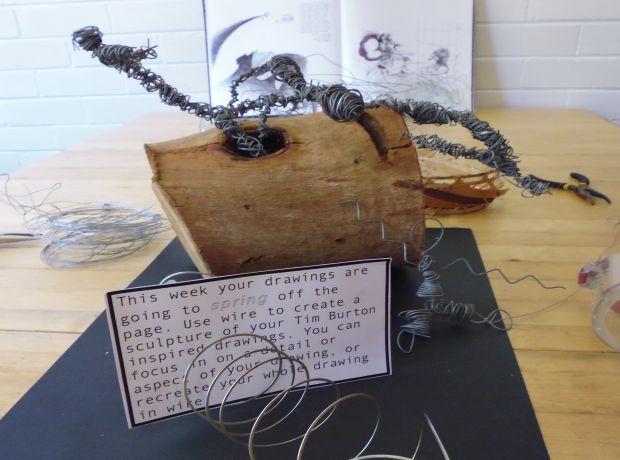

- Representational Development – Consistent with Howard Gardner’s notion of multiple intelligences, the Reggio Emilia approach calls for the integration of the graphic arts as tools for cognitive, linguistic, and social development. For example, questions, concepts and hypotheses are explored through many different forms, e.g. print, art, clay, wire, construction, drama, music, dance, photography, film etc.

- Collaboration – Collaborative group work, in small groups and large groups, is considered valuable and necessary to advance cognitive (as well as linguistic, emotional and social) development. Students are strongly encouraged, by educators and the layout of the physical environment, to work together in small groups and to negotiate with, and act as a resource for, each other.

- Educators as Researchers – The role of the educator is first and foremost to be that of a learner alongside the students – investigating genuine questions together. The educator is also a researcher – a resource and guide who carefully listens, observes and documents students’ work and the growth of community in their classroom; and who provokes, co-constructs, and stimulates thinking as well as students’ collaboration with peers. A fundamental pre-requisite for this learning methodology is a ‘pedagogy of listening’ – always being on the lookout to identify possibilities for deep rich investigation. Educators are also continually engaged in a process of reflection on their own learning and practice.

- Documentation – Documentation of students’ work in progress is viewed as an important tool in the learning process for students, educators and parents, e.g. recording students’ engagement in experiences, combined with their theorizing, debate, reflections and dialogue.

- Environment – Great attention is given to the look and feel of the classroom – the environment is considered ‘the third teacher’, one that offers students ‘invitations’ to learn and ‘triggers’ for research. Educators carefully organise spaces for small and large group projects and small intimate spaces for one, two or three students.

- Advocacy – Educators view students as important members of, and active citizens within, the broader community – capable contributors when they are invited to participate and are listened to. Making children’s capabilities visible to everyone in the community is seen as an important responsibility for adults.

(Overview prepared by Blue Gum Community School, incorporating information from The Hundred Languages of Children travelling exhibition.)

Further information on the Reggio Emilia experience:

Professor Maurice Holt, University of Colorado, Denver, has coined the term ‘slow schooling’ – which takes inspiration from the Slow Food Movement’s reaction in Italy against fast food, and against the globalisation and homogenisation of food around the world. Likewise, slow schooling rejects the flavourless bland fare that is served up as pre-digested learning even when re-packaged by adding addictive entertaining technology. By contrast, slow schooling invites students and educators to come into the metaphorical ‘kitchen’, where apprenticeship alongside skilled mentors invites an appreciation and pride in working towards ‘craftsmanship’ over time by –

- experimenting with the ‘ingredients’ and trying out different combinations; &

- appreciating local home-grown ‘produce’, as well as unfamiliar exotic imports.

Slow schooling is about each student savouring their particular experience and fully engaging in the process of experimentation and research. It is about nurturing what is unique in the local area and culture; and nurturing what is unique and special about each student. It is about students taking the time to explore their world and themselves much more deeply, and to reflect on their findings. And that is very challenging – for the student, and for the people around them, as they try out different ways of doing. Sometimes it can be very frustrating for all concerned. But, it is the process by which they learn to become whole people.

Unfortunately, the current political climate in Australia and many other countries, e.g. USA, seems determined to treat students as though they are products to be processed and tested for quality. The focus is on a centralized, standardized curriculum, which sorts and grades students as though they are cans of beans [which usually get rejected and discarded if they are irregular or fail the test!]. By contrast, slow schools value and promote creativity, critical thinking, resilience, intrinsic motivation, persistence, humour, reliability, enthusiasm, civic-mindedness, self-awareness, self-discipline, empathy, leadership and compassion – attributes that Gerald Bracey’s Report on American education points out, cannot be measured by standardized tests. Instead such attributes vary from person to person, producing a rich diversity of human beings who complement rather than replicate one another.

UK Professor Maurice Holt describes slow schools as places “where students have time to discuss, argue, and reflect upon knowledge and ideas, and so come to understand themselves and the culture they will inherit…..a school that esteems the professional judgment of teachers, that recognizes the differing interest and talents of its pupils, and works with its community to provide a rich variety of learning experiences.” Taking up the ‘slow food’ analogy, Holt says “slow schools give scope for invention and response to cultural change, while fast schools just turn out the same old burgers.”

So, what do we want for our children?

Blue Gum argues strongly that it is time to stop and think about where schools are heading, just as many people are doing in other aspects of life e.g. architecture, travel, art etc. Blue Gum believes schools are important places for students to come to and discover what it takes to be an active community participant, by being an active player in their classroom and their school community (and beyond), instead of a passive recipient of predigested thinking.

In July 2004, the Australia-wide ABC Radio National ‘Life Matters’ program interviewed Professor Holt about the basic principles behind slow schooling. Also interviewed was Blue Gum’s Executive Director, Maureen Hartung, who described some ways in which slow schooling is reflected in the school’s educational approach and has struck a chord with the whole school community.

Slow schooling blends well with Blue Gum’s philosophy, because Blue Gum sees each student as competent, capable, creative, responsible, resourceful and resilient, rather than products to be processed and graded. There are no bells to regulate the day. Students have time to explore in-depth the areas they are researching, rather than superficially skimming the surface of an increasing list of prescribed subjects. Educators take time to acknowledge and build on the wide range of interests and capabilities that each student brings to school – they are shared and explored, so they also enrich the lives of other students.

At Blue Gum, students engage in ‘real-life’ learning experiences, wherever possible, where they work collaboratively to gain an understanding of the world in which they live, and can reflect on current practices and construct better ways of doing.

Blue Gum’s approach to schooling has gained recognition for its successful outcomes for all students. By valuing and celebrating diversity, and nurturing each student’s unique qualities – a process that takes time – Blue Gum has seen students thrive who had been bored or failed by traditional approaches to schooling.

In keeping with the Slow Food connection, Blue Gum has developed a new version of a school canteen – a weekly Blue Gum Kids’ Café that is managed by the students. Each week, one Class takes responsibility for selecting a menu; budgeting & shopping for ingredients; deciding on the venue setting and making costumes, props and decorations; then preparing & cooking a nutritious and delicious shared lunch option for the whole school. The resulting profit is tallied and spent by the Class after discussion e.g. on the Class’ wish-list for equipment/resources.

The opportunities for learning are as diverse as the meals prepared! Students discuss the importance of healthy food choices and safe food preparation, while grappling with moral dilemmas, such as “Do we buy cheaper ingredients, so we make more profit, but end up with a less flavoursome/nutritious meal?”

This slow food experience exemplifies Blue Gum’s integrated ‘real-life’ learning experiences, that are so rich in possibilities, yet so satisfying when students can slow down and take the time to chew on and digest the offerings.

In 2015, Dr Stephen Smith, an academic researcher from Newcastle University approached Blue Gum to spend time observing and researching Blue Gum classrooms in action. The outcome was a lengthy research article – see link to this article below.

Further information on the Slow School Movement:

- Slow Education Down Under: The Slow Education Movement at Blue Gum Community School, by Dr Stephen Smith, Newcastle University, 11 March 2015 – sloweducation.co.uk/2015/03/11/slow-down-and-smell-the-eucalypts-blue-gum-community-school-the-slow-education-movement-by-dr-stephen-smith/

- Laid-back learning, article in The Age newspaper, 1 November 2004 – www.theage.com.au/articles/2004/11/01/1099262769690.html

- It’s Time to Start the Slow School Movement, by Professor Maurice Holt – www.bluegum.act.edu.au/links/Maurice_Holt_Slow_Schools.pdf

“When it’s real work, students do it– no matter what the subject. A lot of the time, though, the work that is done in schools LOOKS like real work, but it is not real ENOUGH… The work must be real. And not what I call ‘fake real’… The traditional curriculum just doesn’t inspire every student to get excited about learning, nor does it meet the expectations of highly motivated or gifted students… A person’s deepest learning usually results from authentic experiences– those whose results really matter to an audience beyond the learner and teacher. Authentic experiences, such as work with a mentor or a community service project, motivate profound learning for several reasons. First, the work has real consequences. Second, the resources for learning are limitless when students are not confined to one building and a predetermined set of materials. Third, a student develops personal relationships with experts in areas of his/her passion. Aside from motivational concerns, a growing body of research indicates that for students to apply knowledge in real situations, they need to learn in those situations. Abstract knowledge gained inside schools is poorly applied by students in real situations outside of school. We learn best when we care about what we are doing, when we have choices. We learn best when the work has meaning to us, when it matters. We learn best when we are using our hands and our minds. We learn best when the work we are doing is real and relevant.” –Dennis Littky, Co-founder of Big Picture Learning. The Big Picture: Education Is Everyone’s Business

“To engage the hand is to engage the mind. Thus, schools must provide for all students a hand-mind approach to the essential ‘academics’. The hand-to-mind pathway is a way to engage all students and deepen their learning, to understand what quality looks like, and through practice and tinkering to apply discipline-based skills. Working the mind without the hands, and without a practice community of adults and young people, produces abstract learners who have difficulty applying what they know to the world around them. Making with hands and minds stimulates young people to develop their imaginative, creative, entrepreneurial, and scientific chops.” — Elliot Washor, Co-founder of Big Picture Learning. Making Their Way: Creating a Generation of “Thinkerers”, Huffington Post, 25/8/10. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/elliot-washor/making-their-way-creating_b_694267.html

Big Picture Learning has been identified by the UK’s Innovation Unit as one of ten school models that are truly designed for the future. The traditional 3 Rs have been replaced by: Relevance, Relationships & Rigour. Entrepreneur Bill Gates is a supporter of this approach, “[These 3Rs are] almost always easier to promote in smaller schools. The smaller size gives teachers and staff the chance to create an environment where students achieve at a higher level and rarely fall through the cracks. Students in smaller schools are more motivated, have higher attendance rates, feel safer, and graduate and attend college in higher numbers.”

Twelve principles or ‘distinguishers’ underpin Big Picture’s approach:

- Academic rigour – ‘head, heart and hand’ – under five core areas:

- Quantitative Reasoning

- Empirical Reasoning

- Social Reasoning

- Communication skills

- Personal qualities

- Learning in the community (real-world immersion learning)

- One student at a time (individualized learning plans, incorporating personal interests and passions)

- Authentic assessment – exhibition/presentation of work, evidencing achievements, challenges and reflections, to an audience of ‘critical friends’

- Collaboration for learning – individual, small group and whole group experiences are targeted for their differing learning opportunities and challenges, especially the value of collaboration rather than competition

- Small core group of 14-16 students with one teacher advisor assisted by a wide variety of specialists

- Culture of trust, respect and care ensures that students are confident in relating to each other and when interacting with adults

- Everyone’s a leader – decision-making is shared

- Families are important contributors to the learning process

- Creating futures – by developing learning and research skills, students are equipped to handle self-directed learning opportunities throughout life

- Teachers are learners and researchers too, modelling this process as they research best practice options

- Diverse community partnerships, e.g. with real-world mentors, businesses, community groups, colleges, universities, TAFEs etc

Blue Gum’s senior students undertake intensive and personally-demanding Community Research Internships (CRI), where they negotiate with an expert/business/community group to undertake a mutually-beneficial authentic research project that is usually off-campus over an extended period. The focus is on real work in a professional setting, which gives the student’s learning context and depth [not to be confused with traditional ‘work experience’ placements]. Each student’s personal control over, and accountability for, their learning is celebrated and assessed through an individual presentation to peers, educators, parents and mentors, who act as ‘critical friends’. As part of their reflection on their sense of identity and acknowledging/nurturing their strengths, as they get ready to transition to larger educational settings, students are encouraged to write/record their own story, following immersion in works of autobiography.

To help all students succeed, schools need to address a much broader set of competencies stretching far beyond the current myopic focus, embracing the whole person – academic, thinker, inventor, fabricator, performer, entrepreneur, citizen – and moving beyond competence to craftsmanship, mastery and artistry. – Elliot Washor

For Russian psychologist, Lev Vygotsky, learning is a collaborative process, involving cultural history, social context, and language. His ‘zone of proximal development’ argues that students can, with help from adults or peers who are more advanced, master concepts and ideas that they cannot understand on their own. The role of the educator is to create the context and physical environment for learning, but then to observe closely students’ interactions with it to see the opportunities for supporting or challenging students to move them to a deeper level of thinking and action. So, an educator may guide students as they approach problems; encourage them to work in groups to think about issues and questions; and support them with encouragement and advice as they tackle problems, adventures, and challenges that are rooted in real-life situations. All members of school community – adults and peers – are both teachers and learners.

How do Constructivist Classrooms differ from Traditional Classrooms?

|

TRADITIONAL Classrooms 1. Curriculum is presented part to whole, with emphasis on basic skills. 2. Strict adherence to fixed curriculum is highly valued. 3. Curriculum activities rely heavily on textbooks and workbooks. 4. Students are viewed as ‘blank slates’ onto which information is etched by the teacher. 5. Teachers generally behave in a didactic manner, disseminating information to students. 6. Assessment of student learning is viewed as separate from teaching and occurs almost entirely through testing. 7. Students primarily work alone. |

CONSTRUCTIVIST Classrooms

1. Curriculum is presented whole to part, with emphasis being on concepts. 2. Pursuit of student questions is highly valued. 3. Curriculum activities rely heavily on primary sources of data and manipulative materials. 4. Students are viewed as thinkers and researchers with emerging theories about the world. 5. Teachers seek the students’ point of view in order to understand students’ present conception/understanding for use in subsequent classes. 6. Assessment of student learning is interwoven with teaching and occurs through teacher observations of students at work and through exhibitions and portfolios. 7. Students primarily work in groups.

|

“Engagement in meaningful work, initiated and mediated by skillful teachers, is the only high road to real thinking and learning. In a constructivist classroom, the teacher searches for students’ understandings of concepts, and then structures opportunities for students to refine or revise these understandings by posing contradictions, presenting new information, asking questions, encouraging research, and/or engaging students in inquiries designed to challenge current concepts… [Increasingly, educators are becoming aware of the complexity of the learning process and the significance and importance of students personally and actively constructing their own meaning.] Examples of such programs include process writing, problem-based mathematics, investigative science, and experiential social studies…”

The case for constructivist classrooms. Jacqueline Grennon Brooks & Martin G. Brooks. New Jersey, Prentice-Hall, 2001.

Social constructivism identifies and accommodates a further dimension – the social context, which frames and shapes our world and our learning.

Positive Psychology & Education

American psychologist, Martin Seligman, has strongly influenced current educational, psychological and management thinking around the world, through evidence-based research. Positive psychology emphasises capacity-building based on individual and collective strengths, rather than deficits; pro-actively targeting positive experiences, rather than reacting after problems emerge; cultivating competency, rather than waiting for pathology; and identifying and nurturing what works well, and replicating it, instead of traditional measuring and testing that focuses on failure. In other words, positive psychology moves the educational lens from a deficit way of thinking to a strengths-based approach to learning and to the development of each student in all aspects of their being.

Traditional education focuses on DEFICITS, not strengths – students are constantly measured and tested against a pre-determined narrow set of skills (a process that is similar to grading cans of beans to ensure uniformity). Students achieving high marks are deemed to be successful students, who are rewarded by being allowed to proceed to the next level of entitlement. Students scoring low marks are labelled as poor learners, and required to keep working at tasks they find difficult, before they can proceed to the next level. The end result of this process, is that a minority of students perform well; are deemed to be academically-capable; and rise to the top of the pile, to be rewarded with a set of ‘keys’ to enter ‘a meaningful and rewarding life’. These are society’s ‘chosen ones’ who fit into the standardised mould and reap the rewards of our traditional education system. Under this model, society is allocating most of its resourcing to enforce a system that isn’t working for most people!

How is a STRENGTHS-BASED approach different? Its starting point is not a pre-determined narrow set of skills (which are uniform); its starting point is to identify the unique qualities / strengths / interests / passions of each person (which differ from person to person). Then the exciting unique learning journey, differentiated for each student, begins. The significant point of difference in using this approach is that every student is successful! The learning program is personalised for each student, so that society’s resourcing is allocated to a system that works for all, irrespective of their individual mix of skills and attributes – there are no ‘waste products’! This allows every student in every Class to develop their own unique life plan.

Areas targeted by positive psychology include: pro-social values, resilience, emotional literacy, relationship skills and ‘personal best’, accompanied by feelings of belonging, safety and optimism.

Further reading –

Seligman, M. (2011). Flourish. London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

Noble, T & McGrath, H (2008)H. ‘The positive educational practices framework: a tool for facilitating the work of educational psychologists in promoting pupil wellbeing’, in Educational and Child Psychology, 25(2): 119-134.

Place-based education emphasises the importance of ‘place’ in constructing knowledge and influencing decision-making and community values. It differs from conventional classroom-located education in that it views the students’ local community as one of the primary resources for learning. So, place-based education promotes learning that is rooted in what is local—the unique history, environment, culture, economy, literature and art of a particular place, i.e. in students’ own ‘place’ or immediate schoolyard, neighbourhood, city or country. The local community and environment offer starting points through which to learn concepts in language arts, mathematics, social studies, science and across the curriculum. Hands-on, project-based, real-world learning experiences increase academic achievement, help students develop stronger ties to their community, and enhance students’ appreciation for the natural world. By being part of identifying and acting on local community issues and events, students become visible citizens who practise caring for and caring about the people and environment they encounter – and importantly, develop a sense of belonging. According to proponents of this pedagogical approach, young school students can lose their ‘sense of place’ if they focus too quickly or exclusively on national or global issues. They stress the importance of students having a strong ‘sense of place’ – a grounding in the history, culture and ecology of their surrounding environment as an essential part of their learning and to provide a sense and understanding of their identity.

Further reading –

Smith, G.A. & Sobel, D. (2010). Place and community-based education in schools. New York: Routledge.

‘Helicopter parenting’ is emerging from the culture of anxiety pervading today’s risk-adverse society. A protective instinct to ‘wrap children in cotton wool/bubble-wrap’ is being challenged by educators and writers such as Clare Warden and Richard Louv, who advocate outdoor play in ‘wild’ environments as a way to nurture curiosity and learning about the natural world, while developing physical capabilities and mental resilience. Louv talks about a growing ‘Nature-Deficit Disorder’ among children (and adults), or alternatively a ‘Vitamin N’ (for Nature) deficiency.

Children all over the world, of every age and in every culture, instinctively connect with and are innately curious about nature. From birth, children’s senses feast on the offerings of the natural world – the sun’s shadow-play in the leaves, the song of a bird or the trickle of a stream. This initial engagement and sense of wonder grows as the child does, if both are nurtured. How does the plant know when to flower? Where do seashells come from? Innumerable questions propel young people to theorise, discuss, debate, illustrate, and form conclusions… to learn.

Traditional approaches to outdoor education focused on risk and adventure, and were imbued with notions of proving oneself ‘against’ the challenges of the outdoors – an adversarial approach. This has changed in line with an image of nature as an ally, rather than an adversary to be conquered. Increasingly, outdoor education is focused on developing an empathetic relationship with outdoor places in response to growing concerns about environmental issues.

Further information –

Richard Louv – www.childrenandnature.org

Claire Warden – www.mindstretchers.co.uk

Brian Wattchow & Mike Brown (2011). A Pedagogy of Place; Outdoor Education for a Changing World. Melbourne, Monash University.